Clans of Caledonia - The Greater Cinematic Franz-verse

Designed by Juma Al-Joujou

Artwork by Klemens Franz

Published by Karma Games

1-4 Players ~ 90-120 Minutes (shorter for solo)

Review by Jack Eddy

In spite of all of its efforts, I really dig Clans of Caledonia.

Yeah, yeah, I know, it’s designed to be enjoyed. Games should be designed to be enjoyed! But the DNA that makes up this game isn’t really my jam. Drawing heavy mechanical inspiration from economic euro predecessors like Terra Mystica, Agricola, and The Voyages of Marco Polo, Clans appears to be a dry, complicated, and punishing game of agricultural domination, which it absolutely is. The big difference, though, is empowerment.

The Economy of Sheep (Gameplay)

Clans of Caledonia effectively boils down to producing resources to fulfill orders. Those resources can either be bought from the market with some hard earned scratch, or you can deploy your pieces on the board. There are two types of pieces, ones that produce stuff: wool, milk, wheat, or cheddar* (*money); or there are factories which change your stuff into bigger, better, processed stuff: bread, whiskey, or cheddar** (**the cheese).

Obviously, putting pieces on the board is the sound investment, but this is a game where every penny counts. Deploying pieces is slow and costly, and with only 5 rounds in the game, it’s hard to gauge exactly how beneficial their production will be.

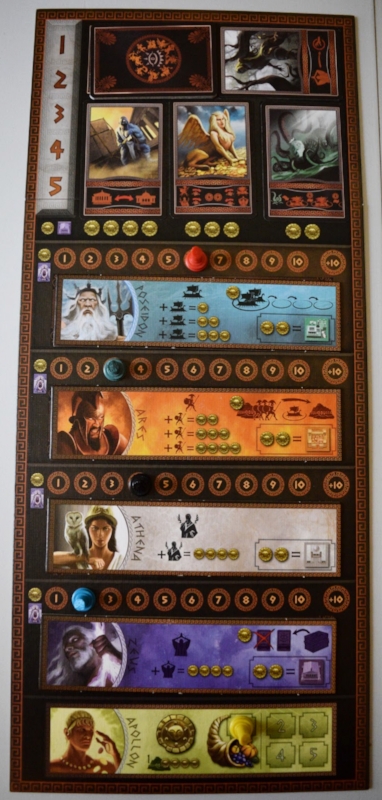

Fortunately, guidance is provided via asymmetric powers. Each player has a clan, and that clan’s powers will often provide general nudges in a direction without entirely dominating a player’s game. Maybe you can buy and sell more goods at better prices, or producing and aging whisky will net you continuous money, or maybe your clan knows the secret and covetted recipe for butter; allowing you to convert milk into hard earned cash at a fixed premium. That said, all of this will usually be in service of allowing you to fill more orders; which is really the major goal of the game.

First off, in order to fill orders, you must have orders, and typically each player can only hold one order at a time. And these orders, requiring various goods including the slaughtering of your poor milk and wool producing livestock, will make up the majority of your points. While each round has its own bonus point award, like 2 points for every deployed worker; the orders give you intangible commodities; cotton, sugarcane, and tobacco. These all score at the end of the game, where the one that players collectively own the least of is the most valuable, setting up a sort of internal economy.

And speaking of economy, the market is by far the most innovative system in Caledonia. Whenever you sell or purchase goods, the monetary value of that good moves up or down. In other words, if you sell tons of cheese, cheese supply is high, which means it will reduce in value. The more people buy wool, the price skyrockets with demand. This imbues you, the player, with the awesome and terrifying power to control the free market, employing it’s whims as an aspect of your economic domination; Milton Freeman would be proud.

Reaping what you sow (How it Feels)

This precision of choices and impact on the internal economy sets up a sort of rhythmic deliberation to the game. You have to really commit to what you’re doing and work with the consequences. That isn’t to say that there is a set path to victory, but victory is reliant on you remaining focused on one objective at a time, chaining consecutive actions together. Get my cows placed here; convert milk to cheese there; purchase a wool, slaughter a cow and fill this order, all so I can start focussing on my next objective.

That said, Clans constantly beckons you to change your plans. Can you really pass up a deal if whisky prices are THAT low? Maybe filling your order would get you some points but the current price of cheese is so high that you’d be a fool not to sell! This is compounded by a proximity bonus that happens when you build next to a neighbor. If one of your pieces is placed next to an opponent’s, you can immediately purchase what their piece produces from the market at a cheaper price. This encourages strategic, clustered, and hopefully mutually beneficial placement on the board.

It’s this precision and immediate impact of your decisions that I love most about the game. Every choice has a consequence for everyone at the table, and you are constantly making meaningful decisions as you build, produce, purchase, and fulfill your way throughout the game. There's a really empowering sense of manifest destiny, trusting that every action is leading to some larger outcome, even if you aren’t always sure what it is yet.

A subjective duality (Art & Presentation)

When I say that Caledonia looks fine, It’s with a degree of bitterness as I compromise the good and the bad. I’ll start off by saying that I really like how the game looks on the table. A lush green and blue world of hexagons adorned with appropriately vibrant and thematic meepl’lified components. Best of all, the game does a phenomenal job at conveying information in a really succinct, intuitive way. So why the duality?

I’m really not feeling the character artwork in this game. Yes, Klemens Franz is a wildly popular artist in the board game biz, and his presence here lends a sort of legitimacy to the first major release by Karma Games, but it just doesn’t really do any favors for the game. While I’ve never been wowed by Franz’ artwork, I’ve respected the sheer amount of work that he’s produced over the years, including, perhaps most notably, the majority of Uwe Rosenberg’s classic games. But in Caledonia, whether it's the juxtaposition of Franz’ characters against the much less stylized backgrounds, or it’s just not his best work, the characters feel disjointed, uninteresting, and out of place.

Don’t get me wrong, if you are a die-hard Franz head, the characters will fit within the greater cinematic Franz-verse, but their integration into the card and box artwork feels out of place, which is a shame for a game that feels otherwise so incredibly cohesive. Fortunately, this never detracted from my enjoyment of playing the game, it just never amplified it either.

An Invigorating Shot (Final Thoughts)

In a surprise twist that I never expected, Clans turned out to be one of my favorite euros of the last few years. Perhaps it’s because, unlike many of its predecessors that it draws heavy inspiration from, it feels restrictive yet never punishing; there are few things that you can do in the game that will fully derail your ability to participate in the rest of the game; some people will call this too forgiving, I call it fun.

Furthermore, the asymmetric powers are subtle but substantial changes, modifying how you approach the game, making sure that each time it hits the table it feels both familiar yet new. Lastly, it plays fantastic at each player count, never really feeling like you are having the compromise the core loop of the game to seat a certain number of players.

That said this game won’t be for everyone. If you absolutely can’t stand economic euro games, steer clear! This is an abstract game of resource collection and conversion, and no amount of forgiving player empowerment is going to change that.

But if you love games with tons of successive decisions, with loads of depth, skill, and (indirect) player interaction, with adorable pieces and great table presence, Clans of Caledonia is an excellent, and surprisingly approachable, entry point into the world of heavier economic euro games.

The Cardboard Herald is funded by the generous support of readers, listeners, and viewers. If you'd like to help support, you can find our Patreon here.

Other Recent Written Reviews: