Elder Sign

Designed by Richard Launius and Kevin Wilson

Published by Fantasy Flight Games

1-8 players 1-2 hours

Review by Cheyenne Morse

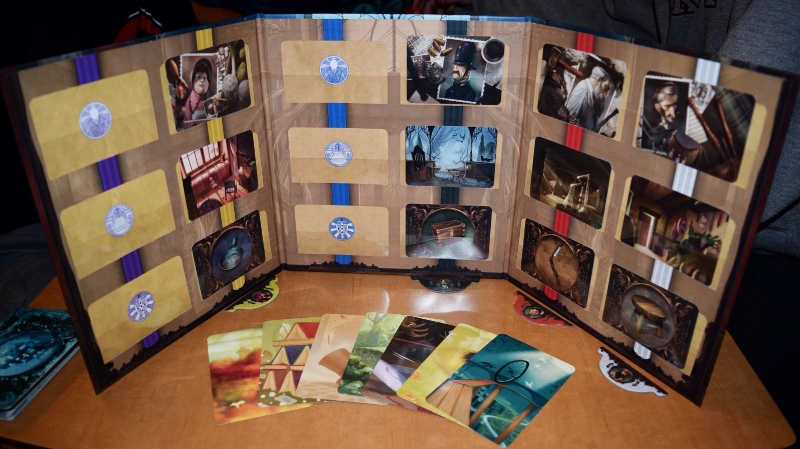

Many games have you wrestling with Lovcraftian horrors, risking life and sanity as you battle creatures from worlds beyond (namely the Public Domain), but my absolute favorite is Elder Sign. Elder Sign is a cooperative dice game in which players try to seal an Ancient One out of the world, using wits, cunning, and a few lucky dice rolls; even as the horrific evil desperately tries to struggle free. Set in Arkham’s Miskatonic Museum, it’s up to players to search each room, battling monsters and crazed fanatics in hope of discovering Elder Signs - the only thing that can save the world.

How to solve a mystery… (Basic Turn Structure)

Each player’s turn starts by choosing an adventure card. These outline the thematic and mechanical goal for your turn, granting rewards including helpful cards, tokens, or the all-important Elder Signs! The various cards and tokens offer boons to future dice rolls or otherwise help your character as they explore the university.

There are monster tokens as well. Monsters are chosen at random during the game and they get added to the adventure cards to increase their difficulty. These get put into play by various means. Sometimes a card will specify a monster is added but it can also be a penalty for failing to complete a task.

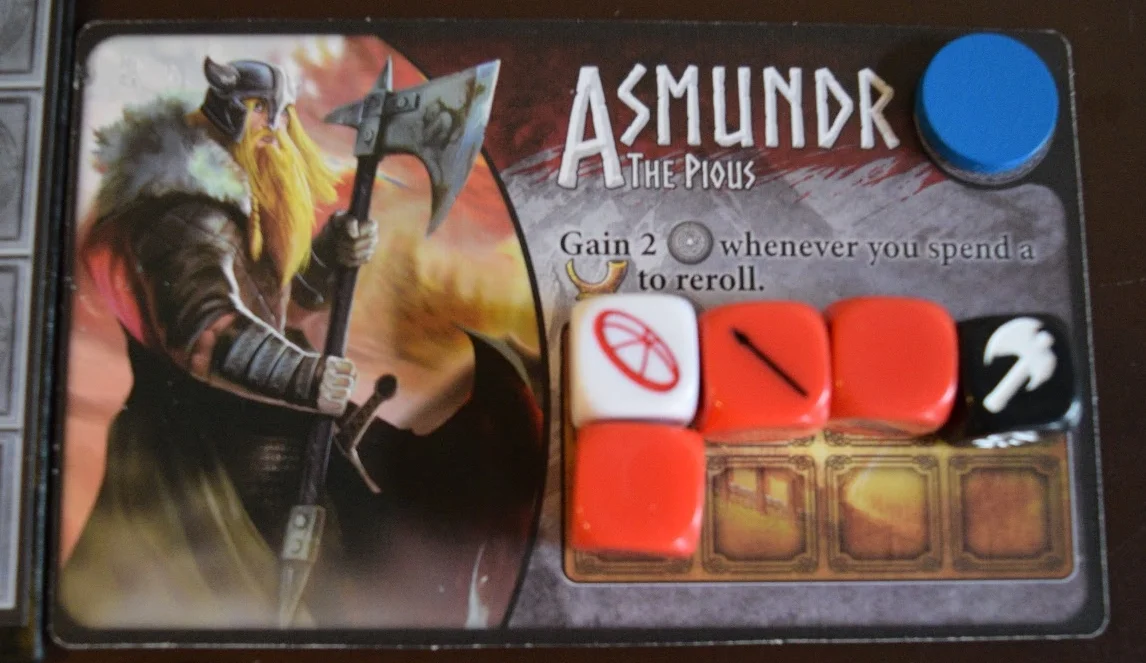

To succeed in an adventure, the player needs to roll dice and match the symbols on the card within a certain number or rolls. Again, this is where the various accoutrements that you’ve picked up can aid you.

Failure results in penalties; usually causing you loss of health and sanity but it can also add on EVEN MORE monsters or progress the Doom track. As I’m sure you’ve guessed, doom is not good; each step on the Doom Track brings you closer to the Ancient One awakening.

Even victory can demand sacrifice. Some tasks can only be defeated by giving up some health or sanity. No one said saving the world was going to be easy.

One of the coolest aspects of the game is the combined use of theme and mechanisms to create a wonderful sense of apprehension. At the close of each turn, the hands of the clock march inexorably towards midnight, at which time a card is revealed and players react to it’s ghastly effects. Usually this means more monsters or another token added to the doom track, signifying the Ancient One’s impending arrival. There is something both delightful and nerve wracking about having a clock counting down to your doom.

Don’t get intimidated

At first glance this game looks complicated, there are lots of little pieces and a couple decks of cards. Often when I’m trying to explain the mechanics to a new player I inevitably get a look of “How am I going to remember all of this” dismay. But the game has a nice flow to it that quickly feels very intuitive, even to beginners. Keep things simple and just run through a couple mock turns, but really that’d help for teaching just about every game...

Read the Cards

I say this for two reasons. The first and most obvious is that you have to read them to know if there are any special effects that take place during a certain phase of the game; such as when the clock strikes midnight or if you roll a Cthulhu image on the dice. Secondly they almost all have text on them that really helps set the tone. It might describe what you hear or see or it might just creep you out. “Memories flooded my thoughts when I saw the thing. I knew I deserved the awful death that it would bring.”

The art is just fantastic. Every time I play I admire the deep colors and stirring images. The physicality of monsters entering the fray can throw your plans into disarray and force the group to change their tactics. Honestly the art is one of the things that makes this game my favorite.

Oh no I’ve been devoured!

Once you run out of sanity or health your character is devoured by the very eldritch horror you’ve been trying to contain. When this happens a doom token is added to the doom track and you say goodbye to your player character along with all the sweet loot you’ve gained over the course of the game. Take a moment of silence for your fallen character and then draw a new one out of the pile. This is a mechanic of the game that I really like. The game isn’t outrageously long but it’s not short either and when a couple of bad rolls of the dice can end your life it’s good to know that you won’t spend the next forty minutes watching your friends have all the fun while you’re slowly digested over a thousand years. Everyone is all in until the end.

The Ancient One Has Awakened

You have failed in your attempt to seal the Ancient One away. It has risen up and is ready to devour humanity. What can you do? Mostly you just die. Each Ancient one has different weaknesses and for most of them you can keep fighting. The chances of you winning are extremely slim but you can always try. Unless it Azathoth, then you and the entire world are just devoured. Om nom nom!

Number of players

This game plays the same no matter how many players you have. It can accommodate small to largish groups of players. You can even play the game solo, face to face with all that darkness, alone as madness slowly consumes you. As a nerd and an introvert this pleases me greatly. Sometimes you gotta go solo against some monsters.

Replay-ability

One of the things that makes this game so great is that it’s a little different each time you play. Since most of the systems in the game are driven by decks of cards, games will feature new and interesting combinations of player characters, adventures, and monsters; all the while maintaining the same overall flow and ease of play.

Overall

This game is super fun to play. It’s the kind of game you can play a lot without getting tired of it. The art is beautiful, there is always a new challenge, and I just love rolling dice. It’s always satisfying! Now go out there and slay some monsters.

Cheyenne Morse is one half of the Fictional Females podcast, which can be found on iTunes, Stitcher, and www.fictionalfemales.com. This is her first ever board game review!